A Chicago man made it harder for rescuers to find him at the Columbia Icefield

“I think the whole event bothered the searchers more than it did me”

George Joachim, September 2013

When asked about the search for George Joachim, the Jasper Parks Canada visitor safety team often sigh and say, “Ah, George.” Four years later, the name still causes concern.

George Joachim, a Chicago resident, went into the Columbia Icefield on 6 September 2009 and disappeared for nine days. Parks Canada spent over CAD 35,000 on the search, which was funded by taxpayers. Joachim was found on the icefield.

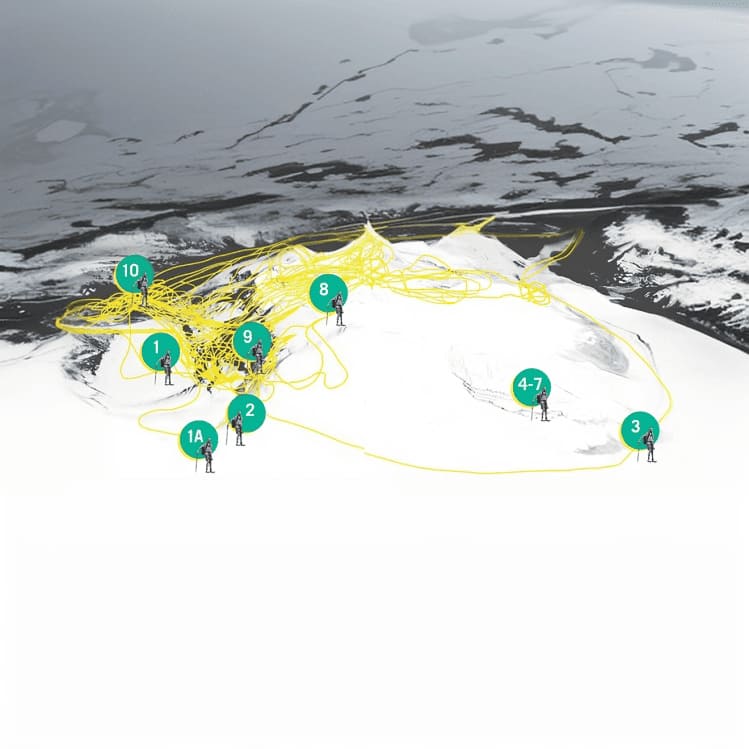

Parks Canada uses a statistical model to help find lost people. The model uses data from similar cases to find the size and location of the search area. The model combines the experience of the searchers and research on the lost person to suggest where the person is likely to be.

Joachim gave searchers the wrong information by listing the wrong place in the climber’s registry. Also, he acted differently from other people in the same situation, which meant that the search team missed a few chances to find him. Parks Canada has learned from Joachim’s case and made changes to its search procedures.

Searching is an art and a science. It is based on clues left behind, statistics, searcher intuition and the environment. This section looks at how these factors came together in the search for George Joachim.

Day one: I’m stuck

George Joachim calls his trip on the Columbia Icefield a “day hike.” He was going towards Mount Snow Dome, having read that the summit was where meltwater flows to the Arctic, Pacific, and Atlantic Oceans.

He was equipped with lightweight survival gear and wore running shoes with crampons. “I had enough food for a day and a half in case I had to stay overnight,” Joachim said.

He parked and signed in at the climbers’ desk. Joachim saw that many people had already signed in to go to the North Glacier. George looked at the map and saw that Snow Dome was in the north of the ice field. I also wrote North Glacier as my destination.

This was a big mistake. The North Glacier is on Mount Athabasca and is usually used for mountaineering training. The distance between Snow Dome and North Glacier is over eight kilometres, so search efforts were focused there.

Joachim followed the glacier tour bus route, ascending the moraine and crossing a packed ice road up the Athabasca Glacier. He says about six bus drivers saw him. Three days later, Parks Canada asked the bus drivers if they had seen Joachim. None of them could remember. Bus drivers often see climbers on this route, which may be why they couldn’t remember seeing him.

Joachim then crossed the glacier until he reached a crevasse field where the Athabasca Glacier meets the main Icefield. Steve Blake, a visitor safety specialist at Jasper National Park in Canada, says experienced mountaineers with the right equipment can get into minor crevasse incidents in the area.

Joachim survived the crossing, but later said he had fallen into crevasses.

It snowed all day. When Joachim left the crevasse field, a storm came in and stayed, making it impossible to see. He thought it would pass like it had before, but it didn’t. He didn’t reach Snow Dome, but he was close.

Joachim was probably about three to four kilometres from Snow Dome (point 1A) at the end of the first day. He cleaned his sleeping bag and bivy sack, dug a hole in the snow, and probably set up above the ramp that marks the start of the Athabasca Glacier.

Day Two: Whiteout around

On the second day, Joachim tried to retrace his steps, but the snow had made the crevasse field hard to see. He chose a different route, going towards the Saskatchewan Glacier. He ended up in a dangerous spot, hanging over a crevasse on the route. “I didn’t fall into the crevasse, but it would take about five miles to get out this way.” “I’m unlikely to reach my destination.” Joachim went back to where he was the night before.

On the second day, a Parks Canada rescue team member checked the climber’s registry, found Joachim was overdue, and told the visitor safety team about it.

Day Three: They’re looking for me

Joachim chose to descend along a ridgeline because of the crevasse and whiteout. The ridgeline was part of an outcropping south of Mount Andromeda. The snow and scree made it hard to find the way. It took me about half an hour to walk half a mile. I was tired and this was a good place to stop. Joachim stayed in a snow band and decided to spend the night there.

Meanwhile, Parks Canada had spoken with Joachim’s family and colleagues and said he was missing. Blake quickly formed a search team, got helicopters, and started gathering information to help find Joachim.

Days 4 to 7: Joachim Profile

The next day the sky was clear and the sun was shining. Joachim says he focused on conservation, energy and food, drying himself out, and that he was in a place where help could be found if needed. He decided the location was perfect for him. He stayed there for three days and nights, thinking he could signal a helicopter that was close by. He was over six kilometres from the North Glacier on Mount Athabasca and seven kilometres southwest of Snow Dome. Darrah calls this an “odd no-man’s land.”

“A lot of it was really pleasant, sunny beautiful days. I had a beautiful view of Mount Columbia. I lay in the sun like a cat, pulled up my shirt, suntanned my back. It’s like, ‘Yeah, I might die, but it’s a pretty nice way.”

Joachim told the Edmonton Journal

Meanwhile, Blake started using the computer model to set the search parameters. “The science is similar to other social and biological sciences. We use lots of data to create different possibilities.” The first step was to find out how much experience Joachim had of mountain travel. This was to categorise him as a subject in the model, for example as a climber, hiker or skier.

RCMP and Parks Canada officials visited Joachim in Fort Saskatchewan and accessed his computer without permission. He had looked online for a route up to the AA col between Mount Athabasca and Mount Andromeda. He was also an active member of online forums where adventurers and survivalists share information. His contributions showed he understood some basic winter travel principles.

The model was added to the search profile, which included missing mountaineer statistics. The model then focused the search on this type of person.

Joachim had no mountaineering experience. I don’t climb. I hike far distances. Joachim says the icefield was “a big flat expanse with a few undulations.” He read that to climb Mount Columbia, he would have to cross a deep valley and then climb up the other side. The climb is not very wild or technical. Many people ski this route.

He showed the right qualities for the job. The most common reason for beginner mountaineers to be missing is that they have become stranded.

However, he was very different. Mountaineers usually follow set routes, but Joachim didn’t know the trails and went to the wrong place.

Mountaineers usually start their trips in good weather and look for shelter when it gets worse. Joachim stayed put on the days the search was most active to dry out and recover.

There was a good chance of seeing George, especially with the fresh snow on the glacier. The light and visibility helped this assessment. Joachim would probably try to make himself more visible. He was in rocky terrain, hidden from view.

Joachim thought he could attract a nearby helicopter if one was flying less than half a mile away. The GPS showed the helicopter flew within half a kilometre of Joachim. Joachim couldn’t see the helicopter, and the search party couldn’t find him.

“It’s hard to see people in this kind of terrain from a plane,” Darrah says. “It’s still hard to find someone even when you know where they are.”

Darrah says that if Joachim had made footprints, they would have been seen. He says this approach has been used to rescue other mountaineers. The rescue team questioned Joachim’s decision not to attract attention. Some rescue team members doubted Joachim wanted to be found.

Day Eight: I’ll get out of here myself

By the eighth day, Parks Canada had found no sign of Joachim. The area was only crossed in snowstorms, so any tracks may have been destroyed.

Darrah says: “Deploying personnel on the ground increased the risk of them being hit by rockfalls and other dangers. The team also checked the crevasse area. “Our team was willing to risk their lives to find him.”

The team’s failure to find Joachim was unusual, given their success in finding missing people. When they had finished looking and found nothing, the case was given to the Jasper Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

The sun had been shining on the slope where Joachim was for three days. The snow was melting and he was worried he would roll down the slope while asleep. He also thought there was a good chance of another storm, which would leave him exposed on the ridge.

He tried to descend the ridge again, being careful not to get too close to what he thought was a cornice. He saw that the terrain was good for building a snow cave.

From here, he saw a way to cross the Athabasca Glacier. The incline was gentle and the sun had melted the snow, revealing the crevasses. If the weather was bad, he would stay in the cave.

I could live in the snow cave for about 20 days. I had 700 calories left. This is about 50 calories a day. After a few days of eating only 50 calories, the person would probably not be able to walk out. This happened at 11,000 feet.

George is back on day 9

On the ninth day, Joachim went back to where he thought he could go down. The ground was mostly scree. I couldn’t go back to where I started. “I couldn’t get out if I got stuck.”

He went down the ramp and crossed the crevasse field, staying close to the rock wall. “I had to go into the crevasses and come out the other side.”

Joachim saw the ice buses had stopped running by the time he reached the packed ice road. He told Blake he’d met a few people on his way out but didn’t stop to talk. He was upset to find his car had been towed. “There was a bag of chips in the car,” he said.

He followed the highway back to the Columbia Icefield Discovery Centre, where he got money for a sweet and called his wife in Chicago to say he was OK. His wife told him the search was over, so he didn’t contact the park until the next day. He spent the night in his bag behind the Centre.

Consequences

Where is my vehicle?

Joachim asked about his car when he got the call the next morning. Darrah’s face showed he was astonished. Everyone was amazed that Joachim was still alive.

Darrah and Blake interviewed Joachim at the headquarters. Joachim was eager to discuss his survival, but the team was surprised by his lack of awareness of the efforts made to locate him and the extent to which his actions hindered these efforts.

Joachim said he didn’t know the dangers and had put the wrong place in the climber’s registry. His behaviour was strange. He stayed where he was. They thought he’d wait out the storm, but he was actually crossing it. This behaviour was unusual for this area.

Blake realised they hadn’t considered something important. At the time Joachim disappeared, footprints were seen at the start of the glacier and after he left the ice bus. Blake says, “We were biased against this route.” It was thought unlikely that someone could cross the dangerous terrain without help, especially without ropes. The footprints were not seen as a clue at the time. We thought they were from other mountaineers.

“We now record our assumptions on the command board,” says Darrah. He adds that searching is about probability. “We have to make assumptions because we don’t have enough resources or time.”

George says there were a few mistakes, but he did the right thing given the circumstances.

I couldn’t get out of the situation, and my actions were the best I could do. When it became clear I couldn’t leave, I stayed put. That was the right thing to do. “When it was safe, I came out.”